phone

cards

all you need to know about

|

|

phone | |

all you need to know about | |||

Mobile Telephone History

Page 8 >>

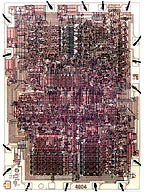

In 1971 Intel introduced their first microprocessor, the 4004. Designed originally for a desktop calculator, the microprocessor was soon improved on and quickly put into all fields of electronics, including cell phones. The original did 4,000 operations a second. According to the June, 2001 issue of Wired magazine, Gordon Moore described the microprocessor as "one of the most revolutionary products in the history of mankind." At the time Intel's chairman Andrew Grove was not so impressed. He reflected that "I was running an assembly line to build memory chips. I saw the microprocessor as a bloody nuisance." Motorola also did much to pioneer the microprocessor and semiconductor field, indeed, in their advertisements of the time, they rightly noted that Motorola circuits were on board each NASA mission since the American space program begain.  In a manuscript submitted to the IEEE Transactions On Communications on September 8, 1971, NTT's Fumio Ikegami explained that his company began studying a nationwide cellular radio system for Japan in 1967. Radio propagation experiments, measuring signal strength and reception in urban areas from mobiles, were ongoing throughout this time, first at 400Mhz and then at 900Mhz. [Ikegami] A successful system trial may have happened in 1975 but I am unable to confirm this. What I can confirm is that Ito and Matsuzaka wrote in late 1977 that "Field tests have been carried out in the Tokyo metropolitan area since 1975 and have now been brought to a successful completion." The two authors wrote this in a major article describing how the first Japanese cellular system would work. [Ito] The First Handheld Cell Phone  On October 17, 1973, Motorola filed a patent entitled 'Radio telephone system.' It outlined Motorola's cellular radio system and was given US Patent Number 3,906,166 when it was granted on September 16,1975. Inventors on the patent were Martin Cooper, Richard Dronsuth, Albert J. Mikulski, Charles N. Lynk, Jr., James J. Mikulski, John F. Mitchell, Roy A. Richardson, and John H. Sangster.  In a 1999 interview with Dr. Cooper, Marc Ferranti, writing for the IDG News Service, describes the competiveness of that era, "While he [Dr. Cooper] was a project manager at Motorola in 1973, Cooper set up a base station in New York with the first working prototype of a cellular telephone and called over to his rivals at Bell Labs. Bell had developed cellular communications technology years earlier, but Motorola and Bell Labs in the '60s and early '70s were in a race to actually incorporate the technology into usable devices; Cooper couldn't resist demonstrating in a very practical manner who had won." [Ferranti] Thus, Cooper claims to be inventor of the cell phone. But the Metroliner service described before was working four years before Cooper placed his call and it was entirely practical. Since the Metroliner used public pay telephones, however, and judging by the photograph here, Cooper may more easily claim, along with his team, to be the inventor of the first personal, handheld cell phone. On May 1, 1974 the F.C.C. decides to open an additional 115 megahertz of spectrum, 2300 channel's worth, for future cellular telephone use. Cellular looms ahead, although no one know when FCC approval will permit its commercial rollout. American business radio and radio-telephone manufacturers begin planning for the future. Here's a chart outlining the major makers. Paul Kagan of Paul Kagan Associates developed it and it appeared in the June 10, 1974 issue of Barrons, in the article entitled "Go Ahead Signal: The FCC has Given One to Mobile Communications." In 1975 the FCC finally permitted the Bell System to begin a trial system. It wasn't until March, 1977, though, that the FCC approved AT&T's request to actually operate that cellular system. [Young] Reasons for this maddening delay was the FCC's overiding desire to control, which Berresford explains like this: "[The FCC] made a series of Solomonic compromises under its 'public interest' standard. A constant assumption in all . . . decisions was that it, the FCC, would decide the issues: whether one or more cellular systems would be allowed in each area; whether telephone companies would be allowed to operate them; who would make cellular telephones and who would sell them; and so on down to technical matters such as whether spacing between voice channels would be 25, 30, 40, or 50 kilohertz.[Berresford (external link)] This delay would cost the Bell System the chance to be the first to offer individuals cellular service. But let's back up a little. After the 1975 trial approval the Bell System put out to bid a contract for 135 cell phones, which they'd use in their upcoming trial in Chicago, Illinois. Competing for that work were five American companies, including E.F. Johnson and Motorola. And also one Japanese company, Oki Electric. The contract went to Oki for $500,000, drawing bitter complaints from the losing bidders and intensifying the rancor between AT&T, now the largest company on earth, and its much smaller rivals. The contract might seem small but in today's dollars it actually works out to $1,598,513. [Calculations] And it points to a more complex problem of the time. Since 1968 Motorola was thought to have spent $13 million dollars ($41,561,338 in Year 2000 figures) on cellular research and development, this cost borne by them alone. Their losing $2 million dollar bid ($6, 394,052, converted, an astounding $47,000 a phone) reflected some of that expense. Joseph Miller, General Manager of Motorola's Communication Division, said that, by comparison, Oki's bid represented "no inclusion of R&D costs whatsoever because these have in effect been subsidized by the Japanese government." Although this was true, it was equally true that unlike American firms, Japan had no defense or space work to spin technology off from. But Miller went further when he said that "Japanese manufacturers, with the financial assistance of their government are now developing systems for their domestic market, but with the clear intent to invade the U.S. market." [Business Week1] One disappointed bidder maintained that by accepting their bid AT&T was further subsiding Oki, and damaging American companies and competition. These were not just idle complaints. The Bell System built and operated the best landline telephone service in the world. It served most medium and large sized cities in America, being the telephone company to at least 80% of the United States population. For all intents and purposes, it was the phone company. By 1982 it employed over one million people! Acting under the largess of a state approved monopoly it built a research and development arm far bigger than any private company like Motorola could ever afford. In the case of cellular AT&T used Bell Labs research, paid for by the Bell System's wireline telephone monopoly, to compete against privately funded wireless companies. Although it had half-heartedly competed with the Radio Common Carriers for conventional mobile telephone service, it was never truly interested in land mobile because too few subscribers were permitted with the limited frequencies available. It didn't make economic sense for so large a company, although the RCCs managed well and treated customers with attention. With the FCC opening new frequency bands, though, cellular radio would be different, with hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions of people as potential customers. While the Bell System could properly contend they owed it to their shareholders to keep down costs, (their Chicago trials wound up costing 28 million dollars, $89,516,728 converted), by not buying American products AT&T appeared to anti-competitive. Well, more so than usual :-) In any case they missed an important first.

|